At Ann Arbor’s chic restaurants, expansive farmers’ markets, and fine groceries, “locally grown” is a selling point, and purveyors highlight the names of farms that supply the fresh fare. But truth be told, most of the food in our supermarkets, cafeterias, and restaurants was grown on massive farms thousands of miles away, just as it is in most American cities. As a former farm owner, I wondered: with the wealth of small farms in our area, why aren’t more of the foods and flowers we see for sale grown locally?

I’ve learned a great deal about the obstacles. But I’ve also learned about how universities, supportive institutions, nonprofits, and business owners are striving to eliminate barriers, develop new channels to connect farmers to buyers, and change wholesale purchasing systems to welcome in a new generation of passionately committed farmers.

—

Michigan State University’s Student Organic Farm south of Lansing is a step in the right direction. SOF’s labyrinthine permaculture garden, freewheeling chickens, and hand-tilled rows seem to stand in direct opposition to the Green Revolution principles of mass-scale monoculture and genetically modified organisms for which agricultural science at MSU was long renowned. Since 2007, the SOF has been turning out a modest but steady stream of new farmers eager to embark on careers in small-scale agriculture. Drawn by our large market of affluent and devoted local foodies, many graduates have started farms in the Ann Arbor area.

None are getting rich. When I recently surveyed SOF alums who graduated between 2008 and 2019, almost half of the thirty-seven who responded reported that they were farming only part-time–an indication that their farms are not producing enough income to support them. This is consistent with national patterns: according to the USDA, half of all farms bring in $6,000 or less. Jeremy Moghtader, farm manager for the University of Michigan Campus Farm, has seen this close up: from 2006 to 2016, he was farm manager and director of programs at the SOF. While existing direct-sales channels such as farmers’ markets may be reaching capacity, “small diversified farmers remain committed to the model,” Moghtader observes, “even when that often requires them to buttress their business with other income streams.”

At this end of the scale, selling wholesale is not the goal. “I think people do this for a variety of reasons, including their love for connecting to the land and to people,” says Moghtader, who has been growing food for his and other families for many years. “Seeing a five-year-old take a carrot right off the CSA [community-supported agriculture] table and eat it, knowing that you’ve been feeding them vegetables you and your farm have been coaxing from the earth sometimes with ease, sometimes with great difficulty, since they were in utero is a powerful thing.”

Today, Moghtader runs a small diversified vegetable farm at Matthaei Botanical Gardens. Students built the three hoop houses and the farmhouse made of straw bales and hand-milled wood. Nearly all the food they grow here is sold to Michigan Dining, but it is one of only a few local farms to supply U-M. “Even in the height of our growing season we haven’t figured out how to get the small- to mid-sized farm products into the wholesale distribution channel,” Moghtader laments.

But if wholesale buyers like U-M were to make purchasing locally grown food a priority, would they be able to source the quantity and quality they require from smaller farms in southeastern Michigan? “Quantity is a big issue,” says Jim Tripp, director of retail, food, and nutrition at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital. “We serve 5,000 meals a day, and to get that supply we’d have to get multiple farms involved if we were seeking local sources.”

St. Joe’s and its parent, Trinity Health, are taking the challenge of buying local more seriously than most institutions. The moment small farms are ready to scale up, Tripp says, he will be ready with cash in hand. Until then, he is working with Grand Rapids-based Gordon Food Service to buy from larger Michigan growers. “If Michigan products are being sold by them, then we will buy them, even if they are more expensive,” he says.

Tripp has the full support of his colleague Amanda Sweetman, Trinity’s newly appointed regional director for farming and healthy lifestyles. Sweetman transitioned to agriculture from a career in natural resource conservation. “I have come to realize that local food is the shiny side of the conservation coin,” she says. “My personal purpose is all about placemaking: how to help people care about where they live so they will conserve it.” At Trinity, “our mission is to be a transforming, healing presence in the communities we serve. We want the local economy and ecology to be healthy. We also want people to be healthier overall, which means constantly improving not just our ability to provide direct health care but also the environment in which people live, play, and eat.”

The Farm at St. Joe’s is a highly visible symbol of that commitment. The little vegetable farm with hand-painted signs is wheelchair accessible to accommodate patients who come to visit or volunteer, and its sales cart in the hospital’s lobby is a wonderful ambassador for local food. But its biggest impact on the local food economy is through the multi-farm community supported agriculture program that Sweetman manages and promotes.

The CSA has tapped into pent-up demand among hospital staff, growing from thirty shares in 2017 to 225 in 2020. Twenty-five percent of the shares are subsidized through a federal program for people experiencing food insecurity.

Membership has grown so fast that the small farms supplying the CSA are struggling to keep pace. “We have scaled back our membership,” Sweetman says. “We order at the 200-unit amount, and we are the largest wholesale account for the small farms in our area.”

—

Robust demand for CSA shares among Trinity’s staff shows how finding new direct-to-consumer connections can expand the market for local food. But for most people, convenience is key, and supermarkets are the easiest place to buy food. Getting products there, however, requires delivery trucks, USDA certification, massive quantities, uniform quality, lower pricing, and targeted marketing–all obstacles that even mid-sized farms struggle to overcome.

Smaller farms and food businesses often rely on local distribution companies, food hubs, and farmer cooperatives to get their goods into larger markets. Eat Local Eat Natural is an Ann Arbor-based local foods distribution company, focusing on meat, dairy, and value-added products.

“We started our business because we knew small producers had challenges getting their product to market,” says Bill Taylor, who owns the company with Tim Redmond, a fellow Ann Arborite with deep ties to the farming community. “A community with a strong local food system has strength and resilience,” Redmond says. “Not only is the local economy strengthened, but community ties are strengthened.” They say sales are strong and have expanded to include products and markets in neighboring states.

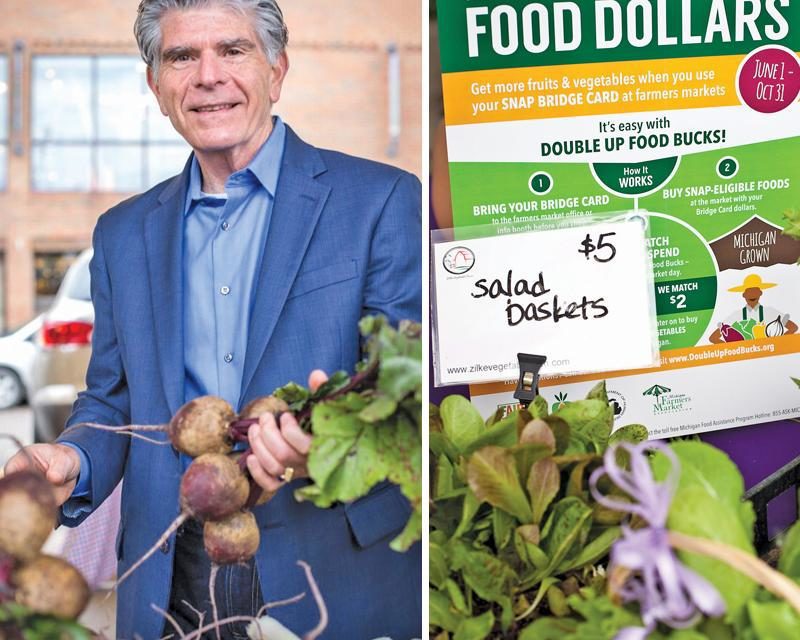

The Fair Food Network, an Ann Arbor-based nonprofit, is pushing supermarkets to break out of their purchasing routines and be proactive in their effort to work with local farms and distributors–and its Double Up Food Bucks program has a large enough client base to make it worth their while. The program doubles the value of SNAP benefits (food stamps) spent on fresh fruits and vegetables.

At first, the program was limited to farmers’ markets, so all the benefits accrued to local growers. But after a few years the organization realized that the majority of shoppers still preferred the convenience of a storefront.

Double Up’s grocery store program was introduced in 2013. At first, it was limited to locally grown food, but that was hard to find among the rest of the produce in the store. So in 2017, the rules were changed to allow Double Up dollars to be spent on produce from anywhere.

Grocery store sales spiked from $400,000 in 2016 to $3.1 million in 2017, roughly double what was sold through Double Up at farmers’ markets that year. And since founder and CEO Oran Hesterman wanted to maximize the benefit to local farms, he added a caveat. “We then told the grocery stores that if they want to participate in Double Up, they need to get a certain percentage of their products from local sources,” he says. “Most of them went for it and put in the work required to find out where the food comes from. Our goal in 2018 was 18 percent, and [it went] up from there.”

In 2018, the amount spent on produce via Double Up reached $5.8 million. “We know Michigan grocers are purchasing more produce and increasing local sourcing as a result of Double Up,” says Hesterman. That year, during peak growing season, participating stores sourced $1.7 million worth of Michigan produce, accounting for 16 percent of all their produce purchases. That was short of Fair Food’s goal, but they’re continuing to work to expand it–and now the goal is 20 percent local produce.

Getting their products to grocery stores remains an obstacle for many small farmers. “Some supermarkets are able to take direct delivery from local farmers, and some are not,” Hesterman has learned. “Usually the larger markets have a central warehouse, and they have to work with distributors and brokers. I think it points to the need for a food hub–aggregation and distribution for smaller farmers.”

Farmer cooperatives can serve the same purpose. “The traditional farmer cooperatives–Land O’Lakes, Sunkist–we think of them as corporations, but they are farmer-owned co-ops,” Hesterman points out. “They started small.”

Although producer cooperatives and food hubs are the most common ways for farmers to collaborate to serve larger wholesale buyers, there are no traditional food hubs in Southeast Michigan, and there is only one cooperative. I know the Michigan Flower Growers’ Cooperative well, because I cofounded it in 2017 with local farmers Amanda Maurmann and Alex Cacciari. To help flower farmers reach wholesale buyers, the co-op hosts a weekly marketplace at the Growing Hope Marketplace in Ypsilanti.

In season, the market floor is filled with a bounty of bodacious blooms with alluring names like Sensual Touch and Raspberry Sundae. Artistic floral designers are the co-op’s best clients and can be seen perusing the aisles, sighing with delight. They are often shopping for millennials’ weddings, with large flower budgets meant to reflect the couple’s belief in sustainability and supporting small businesses.

Co-op board president Adrianne Gammie, owner of Marilla Field & Flora, says that while locally grown flowers are more expensive than what florists get from mega-farms in South America, they are worth every penny. “Local quality is unsurpassed,” she says. “Flowers, especially ones grown locally, give us a tangible connection to the world around us. They ask you to stop for a moment and consider just how magnificent our world is.”

Wildly creative floral arrangements are among Instagram’s hottest feeds, and consumers are taking note. The co-op is slowly winning over wholesale and brick-and-mortar florists by helping them keep up with design trends through samples and invitations to events.

“There are so many flowers that are grown commercially on the West Coast, but that just don’t travel well to Midwest,” emails Andrew Arthur, a co-op board member and Detroit-based buyer for flower wholesaler Nordlie. Now that they’re available locally, his customers would rather buy from Michigan growers.

—

Farmers unable to organize their own means of aggregation and distribution are fortunate to have Jae Gerhart, local foods coordinator with MSU Washtenaw County Extension Office. A graduate of the SOF, Gerhart stepped into the newly created position in 2016 after years working for local food and agriculture businesses, including a three-year stint at my own farm.

“One of the most exciting parts of my job is to broker local food deals–I’m essentially a local food hustler,” she laughs. For example, “farmers will call me in the peak of the season telling me they are drowning in tomatoes, and it’s my job to find chefs or grocery-store buyers who will purchase them. Main Street Ventures was a fantastic partner. Last August, when the tomato supply locally was extraordinarily high, Chef Brent [Courson] purchased hundreds of pounds of beautiful heirloom tomatoes to use in his restaurants Chop House, Real Seafood Company, Gratzi, Palio, and Carson’s.”

Gerhart feels lucky that MSU enables her to make those connections for farmers without charging a commission. “If you’ve ever met a farmer, you’ll know how incredibly hard they work,” she says. “If I can help them more easily navigate one part of that equation, I know I’ve done my part.”

The Washtenaw Food Hub is doing its part, too. As a “triple bottom line” business, it aims to create social and economic benefits as well as financial gain. Owned by Richard Andres and Deb Lentz of Tantre Farm, the sixteen-acre property on Whitmore Lake Rd. has ten buildings, including a beautiful timber-framed event and market space that is opening this spring. It also boasts three certified kitchens and a large cooler–plenty of infrastructure to move a lot of local food.

The Hub serves as the processing and distribution point for the Brinery and Harvest Kitchen, two locally owned food businesses that incorporate hundreds of thousands of dollars in local produce, meat, and grains into sauerkraut, pickles, and home-delivered meals. Both businesses work with distributors to reach larger markets, but Andres may expand the Hub to handle marketing and distribution for local farms and food businesses seeking to expand their reach.

The slow and steady approach has worked well for the couple. Tantre is among the most enduring and beloved diversified farms in the region, and they hope to see the Food Hub’s role grow in years to come.

“Wes Jackson has a quote that hit me this fall,” Andres reflects. “If you can finish your life’s work in your lifetime, then your vision isn’t big enough.”

———-

from the April 2020 Ann Arbor Observer

To the Observer:

Thank you for a great set of articles on our local food situation [“Farming 2.0,” February, and “Scaling Up,” March]. This is a challenge about which we care a great deal.

We and our customers have certainly been curious about the reason for the omission of Argus from the last article. I think the confusion comes from the [sub]title of the article: “Everyone says they love local food. So why is it so hard to find?” This has been the exact premise of Argus since inception. For consumers, local food is now extremely easy to find– just go to Argus any day of the week, all year long. I think this is why Argus customers reading this article have been scratching their heads.

As we look to quantify our impact, the statistics that you identified in the article are extremely helpful:

“… half of all farms bring in $6,000 or less.” At Argus in 2019 over 30 farms brought home more than $6,000 in payouts from their sales. The average payouts were over $20,000 for these farms. In total, we just passed the cumulative milestone of $10 million in local sales, of which $6.5 million has been paid out to local farms and producers.

“… for most people, convenience is key, and supermarkets are the easiest place to buy food. Getting products there, however, requires delivery trucks, USDA certification, massive quantities, uniform quality, lower pricing …” All true, unless you live in Ann Arbor, and can shop at Argus, where farms take home 75% of their retail sales (5 times higher than the national average).

Double Up stores sourced 16 percent of their produce from Michigan in 2018, “short of Fair Food’s goal … and now the goal is 20 percent local produce.” Argus had the highest percentage of any Double Up store in Michigan, at 100% local. Argus is the only Double Up grocery in Ann Arbor that is open year round, and when the Double Up program pauses each year in April-May, we have found alternative funding to continue the program at full value for customers. We have engaged a graduate student on a project to expand utilization of the program at Argus.

We hugely appreciate the local food initiatives mentioned in your article. It is going to take all of us, pulling together, to turn the tide and create our own version of a vibrant and sustainable local system.

Sincerely,

Bill Brinkerhoff

—

As Brinkerhoff surmised, we were focused of the scarcity of local food in wholesale channels and chain supermarkets. We’re sorry to have slighted Argus and other independent grocers.